Image 1 of 1

Image 1 of 1

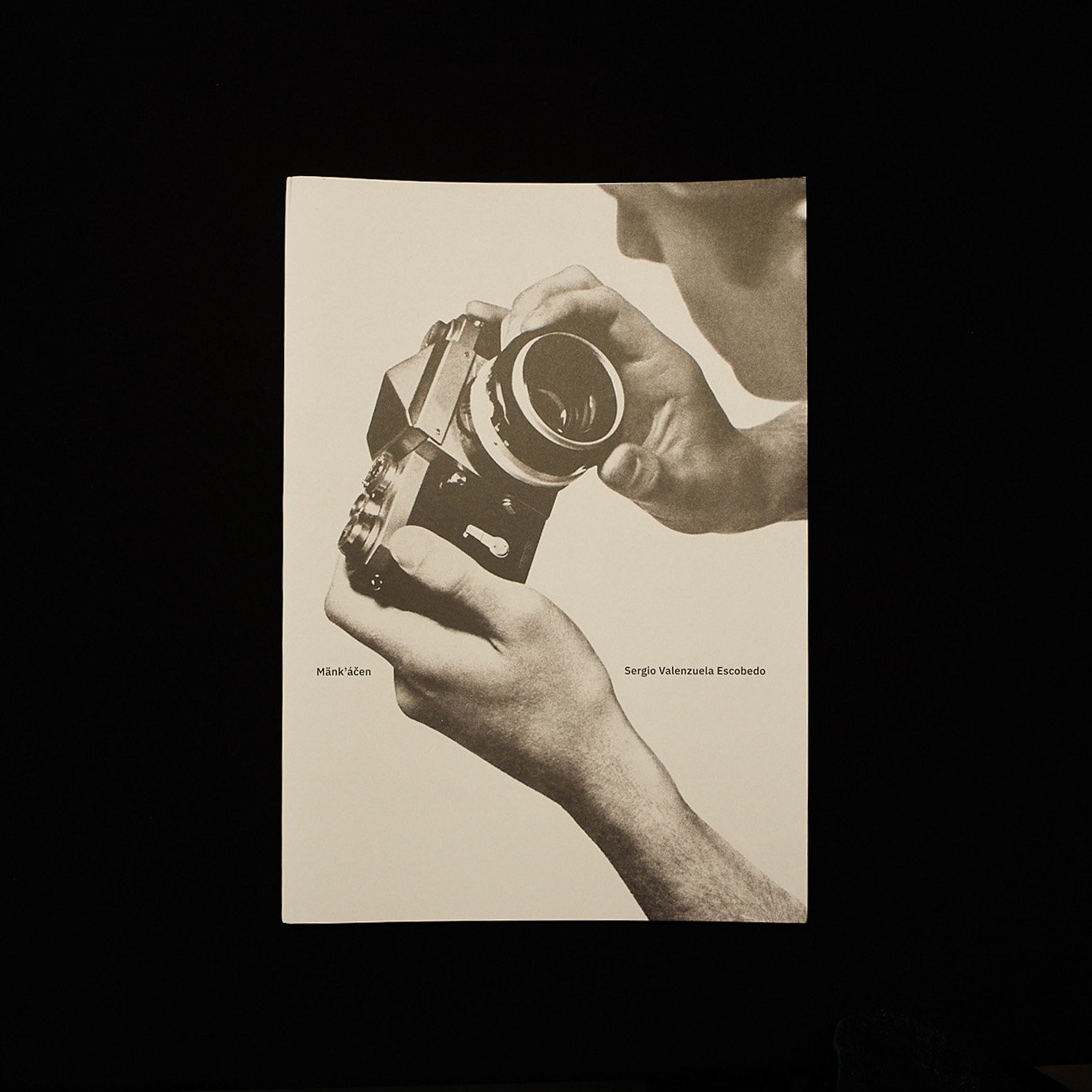

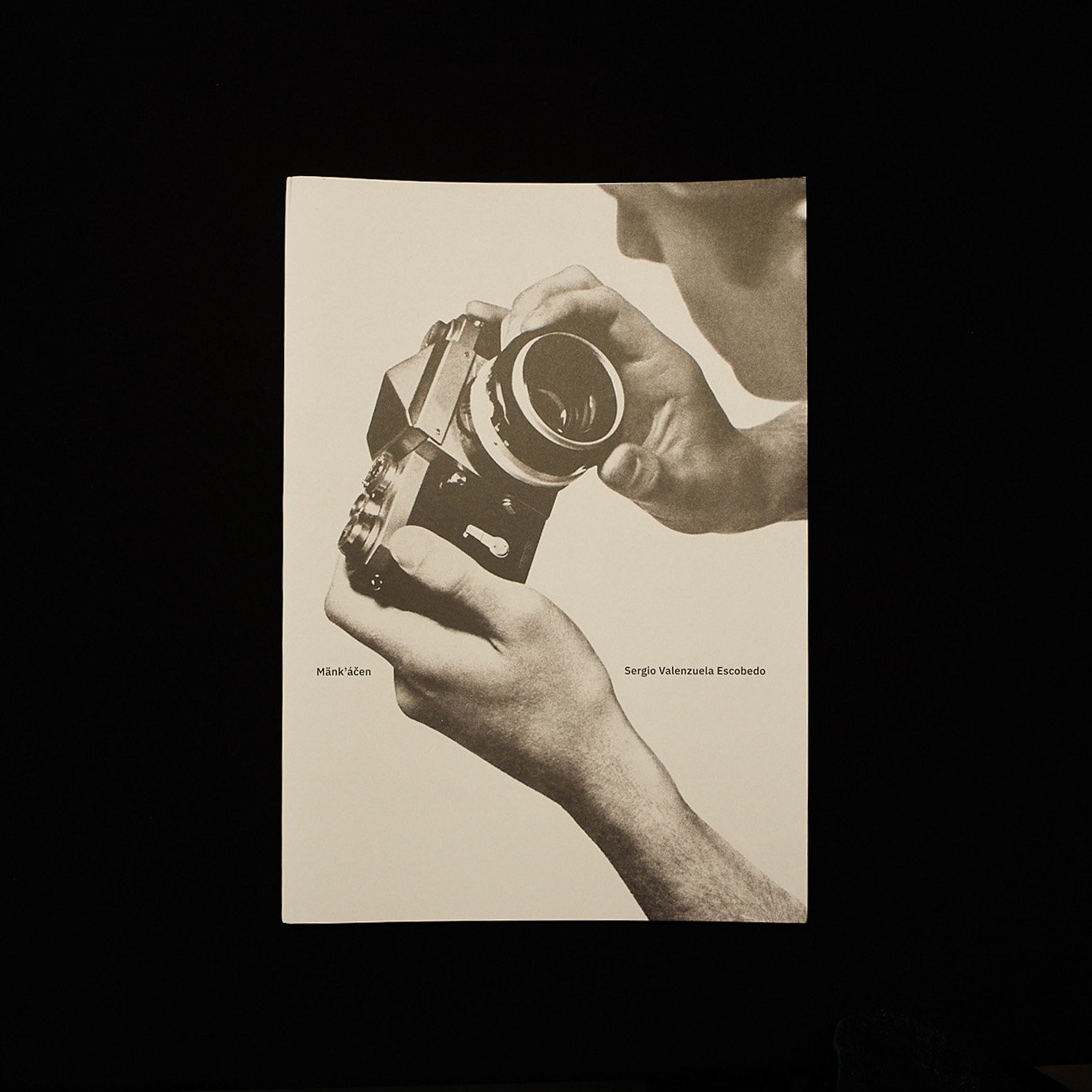

MÄNK'ÁČEN - Sergio Valenzuela Escobedo

Toumayacha Alakana: this expression is the origin of this work by Sergio Valenzuela Escobedo, which led to the completion of a thesis in photography. It means "to look at the head covered with a veil".

This is how the Fuegians named the act of photography in the 19th century, when they saw the first cameras with the operators who landed in South America as early as 1840.

What names did the local peoples give to these new image-objects? How was this unknown tool perceived? What did it mean to be looked at with a veil over one's head?

European photographic collections showing these ancestral Americas bear witness to colonialism and the socio-political context of the countries concerned in relation to "indigenous" communities. The latter have partly lost their culture, their economic and territorial autonomy.

But they also bear witness to an unprecedented history concerning not only the use of technology, but also the relationship to the knowledge and beliefs that characterize the culture of these peoples at the "end of the world", as well as the conditioning of our view and knowledge of these same peoples. It's a colonial myth that Amerindians don't want to be photographed, particularly because we're "going to steal their souls"; this Western belief gave value to the images brought back by explorers. The issue of camera refusal is much more complex and varied: resistance can relate to the taking of the picture, to the circulation of the self-image, to the one-sided nature of the transaction, to a lack of understanding of the camera, as well as to political and spiritual consequences.

Mänk'áčen ("the shadow hunter" in the Yahgan language) thus presents the findings of artist/researcher and curator Sergio Valenzuela Escobedo, and also draws on an ethnographic archive to defend the thesis of the existence of a "mystical mechanic"; text by Justo Pastor Mellado.

Published by Palais Books, 2022

24 cm × 34 cm, 40 pages, new

ISBN 9782493123039

Toumayacha Alakana: this expression is the origin of this work by Sergio Valenzuela Escobedo, which led to the completion of a thesis in photography. It means "to look at the head covered with a veil".

This is how the Fuegians named the act of photography in the 19th century, when they saw the first cameras with the operators who landed in South America as early as 1840.

What names did the local peoples give to these new image-objects? How was this unknown tool perceived? What did it mean to be looked at with a veil over one's head?

European photographic collections showing these ancestral Americas bear witness to colonialism and the socio-political context of the countries concerned in relation to "indigenous" communities. The latter have partly lost their culture, their economic and territorial autonomy.

But they also bear witness to an unprecedented history concerning not only the use of technology, but also the relationship to the knowledge and beliefs that characterize the culture of these peoples at the "end of the world", as well as the conditioning of our view and knowledge of these same peoples. It's a colonial myth that Amerindians don't want to be photographed, particularly because we're "going to steal their souls"; this Western belief gave value to the images brought back by explorers. The issue of camera refusal is much more complex and varied: resistance can relate to the taking of the picture, to the circulation of the self-image, to the one-sided nature of the transaction, to a lack of understanding of the camera, as well as to political and spiritual consequences.

Mänk'áčen ("the shadow hunter" in the Yahgan language) thus presents the findings of artist/researcher and curator Sergio Valenzuela Escobedo, and also draws on an ethnographic archive to defend the thesis of the existence of a "mystical mechanic"; text by Justo Pastor Mellado.

Published by Palais Books, 2022

24 cm × 34 cm, 40 pages, new

ISBN 9782493123039